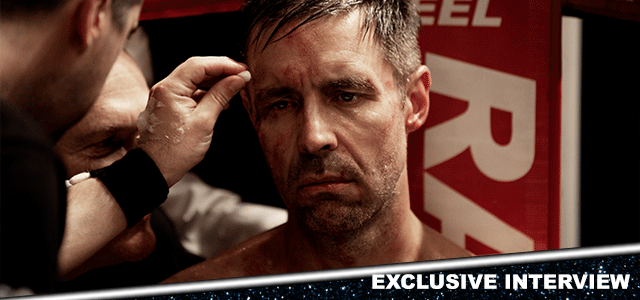

Few actors are capable of emitting intensity quite like Paddy Considine. From his early days collaborating with Shane Meadows in A Room for Romeo Brass through to the likes of In America and Peaky Blinders, he's amassed a formidable body of work, and not just in front of the camera.

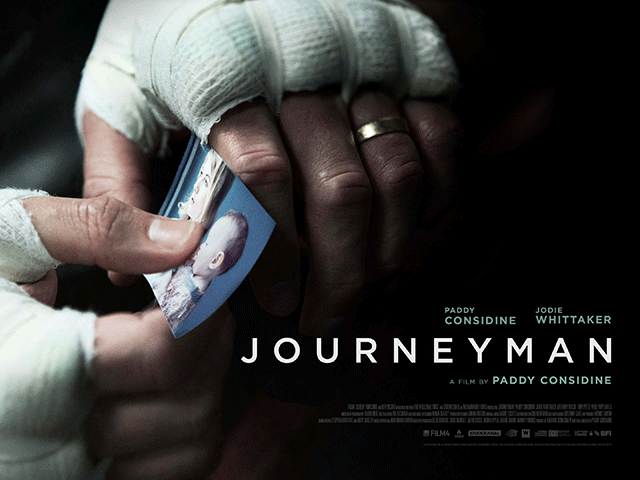

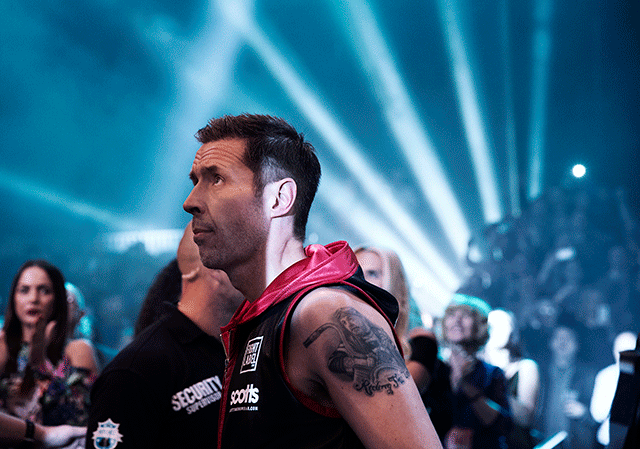

In 2011, he made his directorial debut with harrowing drama Tyrannosaur, and now Considine is back with his new movie, Journeyman, on release in selected Cineworlds from this Friday. He writes, directs and stars as world championship boxer Matty Burton whose decision to defend his title has drastic consequences when he suffers a life-altering brain injury. What then ensues is an agonising road to recovery, as Matty struggles to recall memories of his loving wife Emma (Jodie Whittaker) and his young daughter.

We were delighted to catch up with Paddy to discuss the elements of the quintessential boxing movie, Whittaker's casting and the legacy of his film Dead Man's Shoes.

So Journeyman is about a boxer and it starts with a boxing match, yet centrally it’s a love story between a man, his wife and their young daughter. What particular aspect drew you to writing the script in the first place – was it a desire to make a boxing film or a love story?

Yeah, it started off with me taking ideas down about a boxing story because it’s a sport I’ve been a fan of for many, many years. So somewhere in the back of my mind, I thought I’d always explore the terrain of a boxing film. But I knew that I didn’t want it to be a typical boxing movie with all the archetypes like the redemption through the fight, one man battling his demons and so on. I wanted it to be something different.

Then it became the story about the brain injury, which I thought hadn’t been explored in a film. It started to become a commentary about what happens to an injured athlete when the crowds go away and it’s left up to him and his family to pick up the pieces. He has this scattered brain. So it became a story about his recovery, but I always wanted to make a love story in the classic sense.

So Journeyman deals with lots of different issues on lots of different levels but one of them, from the character of Emma’s point of view, is that the man who returns home after the fight isn’t the man she married, he’s taken on a completely different identity. In taking that on, I wondered how much their love could be tested before she breaks. Because brain injury changes your behaviour. There are a lot of childlike qualities that can emerge. Some people can hit out and be violent, there’s a lot of frustration and anger, because they’re not expressing themselves as they did pre-injury.

I wondered, how does someone cope when the man they married is gone? It’s the same vessel but it’s almost like the person is a stranger now. It was a story that tested their love and commitment to one another. Ultimately, what motivates Matty to come back round is the love of his wife and his daughter. It’s classic storytelling but as far as boxing and boxing movies were concerned, I thought it had all been explored. There’s no point in making another movie like that because – well, how do you make one in the first place? It has to be about something, and boxing itself isn’t a subject matter. It’s always about the people.

The match itself occurs at the very start of the movie, and from my point of view, I felt it was Matty's own life that subsequently became the equivalent of the arena. His own existence is what he has to battle with. Was that a deliberate decision on your part?

Yeah, for sure. In a lot of boxing movies, the fight is the penultimate thing, it’s the redemptive part of the story. I was very dogged about getting the fight over within the first act. Then the fight really does begin when they’re at home when the recovery begins and the crowds have all gone away. It becomes very brutal because they’re in this house, which from the outside looks like success, but it becomes a prison for them all.

I just wanted to portray the struggle that people don’t see. They see the turmoil and struggle of the fight, but not the recovery process. It’s the situation post-trauma. And this is universal. It’s not just specific to boxers, brain injury occurs in a lot of different scenarios. But ultimately, it is a film and a love story.

As a kid, I’d sat and watched The Champ with Jon Voight. I think it was one of the first times I’d ever sat and looked at people in my family and they were all crying. And I was crying too. In that moment, I understood the power of storytelling and that it has the potential to transform you, to bring those emotions out in you. I had that realisation very young.

This is the first film you’ve directed since Tyrannosaur, back in 2011. How did the gap between the two films aid your development as a filmmaker?

I think I was always potentially going to be a director. Early on I’d worked with a filmmaker called Pawel Pawlikowski who was encouraging and must have sensed that I would be making my own films one day. He would introduce me to people and say, "This is Paddy, he’s an actor but will be making his own films one day". I thought that was great of him, that he sensed potential in me early on.

But my experience in front of the camera, that was a given. And I’d been on enough film sets and watched enough films to understand how to create and put a story together. I have my own mantras and ways of communicating with actors. I developed a language of my own and there was just this real urge in me to want to tell stories. By the time it came to Journeyman, I was very much ready to make my second film.

I was scared of doing it, but I think that’s quite healthy. Every time you take on a project, you’re creating this little separate world for everybody to step into. You’ve got to go in there, honour the project and leave your ego at the door. You’re not the master of it anymore, you’ve got to be subservient and follow it, you know?

It’s an interesting thing because when Matty makes the decision to defend his world title, there is a distinct sense of fear hovering in the background. Yet he doesn't let fear overwhelm him. As an actor, is that same element of fear a vital thing in terms of making risky creative decisions?

I think it is. You have to be careful with fear that it doesn’t consume you. A small amount of it is healthy but it can get too overwhelming. But I’m a great believer in having to face your fears, and they’re never as bad as what’s in your head. I did my first theatre production this year and it ended up going to the West End for a 16 week run. I’d never done theatre before and I was absolutely terrified. I felt like I didn’t belong there and that I was a phoney. Why don’t they get somebody else who’s done theatre before and so on. Well, I did it because they asked for me, and you’ve just got to accept the job and get on with it.

Fear’s grand but you can’t let it control things. One of the reasons why I initially wasn’t going to play the lead in Journeyman was because of fear. And also it was down to what people would think. You know, I’m acting in it, writing it and directing it. Everyone will think I’m a show off. But then I think, well no, this is what I do. If somebody else had come to me with this part, I wouldn’t have thought twice about it.

To be honest with you, and I haven’t said this to anybody else, I’ve been in a lot of films where I’ve been a sub-character. I haven’t been offered a lot of lead roles. And that’s frustrating too. You want some great lead parts to come up and you’re not getting anything. So I thought it was time for me to step up and take control of that a little bit.

Just to go back to the boxing itself. There’s a quote from Martin Scorsese in which he says he compared the fights in Raging Bull to a game of chess. He wasn’t interested in boxing so much as its visual potential. How did you approach that sequence in your movie?

That was the thing that haunted me the most. I don’t think you can make boxing look real in a film. They’re not hitting each other for real. Scorsese did such a magnificent job of lending a different tone to each fight. And he didn’t try to make the boxing look authentic. He tried to make it look cinematic. That’s a totally different thing, and a very smart thing on his part.

There’s one part in particular where Jake LaMotta fights Sugar Roy Robinson and the ring is literally smoking. It’s like an inferno. He very beautifully and artistically handled it in a totally different way. It wasn’t looking for authenticity so much as the experience of each fight. But if you try and make it realistic for the camera, it always looks like a stunt. It always looks choreographed. No matter how great the choreography is, it always looks like a dance.

Rocky, meanwhile, treated it completely differently. But I still thing it’s the greatest depiction of boxing ever. Purists may disagree and look at it and think Rocky’s a terrible fighter. But for me, it was always about how the fight married with the potential of the script. It was narratively exciting, and it worked. You were in there, rooting for Rocky to get to that final bell. I think very few films have been able to recreate that.

So I knew I couldn’t make the boxing look real. I’d have to get hit to do that and I’d have to punch my co-star Anthony Welsh. I had a nutritionist for the film, because I had to go on a diet and get in shape for it. He said why don’t you just get in the ring, turn the cameras on and just smack each other for 10 minutes? I said we can’t, we won’t even make it until dinner time. I was sparring in preparation for the film and got my ribs smacked. I was then nursing damaged ribs leading into the production of the film. Even when shooting the fight scenes, I still had a damaged rib. I said to him, I simply can’t do it because I have to get through six more weeks of shooting and by the way, Anthony and I are actors. We don’t want to knock lumps off each other.

After 10 hours of filming, my nutritonist came up to me and finally understood what was at stake. It takes literally hours just to get a couple of minutes of usable footage. There are ways in which I perhaps could have done the fight better, but I wanted above all to depict the intimacy of the experience, because I knew I couldn’t possibly make it look real.

Your depiction of Matty's rehabilitation is both harrowing and inspirational. What research went into the physical mannerisms, in particular the ways in which he holds his hands?

I went to Headway brain injury charity in Henley and sat down with some people there who had suffered brain injury. I was able to observe them. They sit around in groups and do colouring and play games, and it’s a place where they can go to have a social life. So I spoke to them and observed the sheer amount of effort needed to simply colour in a picture. I picked up various mannerisms from that experience.

But there’s also a lot of documentation out there. There’s a documentary from years ago called A Stranger in the Home, which is about a head trauma patient coming home and you can see very much how it altered his personality. There was a documentary on Orange Juice musician Edwyn Collins called The Possibilities are Endless, a beautiful film, and that was another huge inspiration to me. I also worked closely with a case study in Sheffield who very generously shared experiences of what life was like with her partner, some of the volatile situations they were in. That was very informative when it came to structuring the second act of the film.

Ultimately, with Matty, it’s absolute frustration he’s experiencing. He doesn’t know who he is, he’s scattered and can’t piece together memories. Then, slowly, after looking at photographs and reliving what feels like the same day over and over again, he finally starts to get some cognition. A sense of memory and identity that relates to the person he once was.

Jodie Whittaker plays Emma in the film and she’s fantastic in it. How important was she to the project?

Well Jodie... She’s very naturally gifted. Very intuitive. And very authentic too as an actor. They’re all the qualities I wanted for the character of Emma. I also wanted both characters to feel like they had a history together. As if they had been together since their late teens or early 20s.

This is not a detriment to Jodie but she has the same qualities Olivia Colman has in Tyrannosaur, in that they both feel like very approachable people. Jodie feels like someone you could have gone to school with. There’s a familiarity and she’s not aloof in any way. I knew she could act but, like anything, you’re crafting this story together and you give a few little notes here and there. But a great actor will take those in and make the slightest adjustment.

All I say to any actor who works on my films is leave your ego at the door and don’t be self conscious. This isn’t about any of us, it’s about the story. Jodie was just great.

Last question, and it’s the inevitable Dead Man’s Shoes one. I first saw this at university a couple of years after it came out and it knocked me sideways. Just the sheer atmosphere and conviction of it. What do you think it is about that film that continues to resonate?

I don’t know, I mean, it’s some years ago now since we made it. 14, nearly 15 years, I think? I think it’s just a classic story. It’s that classic revenge story that the people identify with, and also the themes of bullying and redemption. They’re very human instincts. We try to suppress them sometimes to be decent individuals, but it’s hard.

Also, it’s a very accessible film. We’re not walking the streets of New York making Death Wish. It’s in a small Derbyshire village that the story takes place, so it speaks about those small town characters. I’m clutching at straws though, really. It’s nice to know you’ve got a piece of work that’s now found another generation.

Click here to book your tickets for Journeyman, opening this Friday, and don't forget to tweet us your favourite Paddy Considine movies @Cineworld.

.jpg)

.png)